| The Future of Custody Law Reform|Law Blogs|

At the current time there is a professed aversion to custody “labels” in legal circles, coupled with a shift of emphasis from deciding who gets custody, to deciding how parental decision-making and time with children will actually be structured between two parties. The latter is sometimes described as a “shared parenting” paradigm.

Insofar as it forces courts to make particularized determinations in preference to declaring all-or-nothing outcomes, shared parenting legislation can be viewed as a positive development. As I have demonstrated in a previous blog post, though, the custody “label” really does continue to matter even after shared parenting legislation is enacted.

Insofar as it forces courts to make particularized determinations in preference to declaring all-or-nothing outcomes, shared parenting legislation can be viewed as a positive development. As I have demonstrated in a previous blog post, though, the custody “label” really does continue to matter even after shared parenting legislation is enacted.

This is why shared parenting legislation typically requires shared parenting orders to make a custody designation, even if it is “solely for the purposes of enforcement.” Short of a nationwide (and worldwide) agreement to abolish custody designations, it will continue to be necessary for courts to address who gets custody, no matter how hard judges and legislators try to deflect attention away from that problem.

The injustice that gave rise to the movement for presumptive joint custody cannot simply be wished away.

It may b e possible to subdue the problem by ignoring it for a while, but at some point it will become necessary to address it head-on. When that time comes, it will be useful to have an understanding of the key issues that need to be addressed when considering presumptive joint custody reforms.

e possible to subdue the problem by ignoring it for a while, but at some point it will become necessary to address it head-on. When that time comes, it will be useful to have an understanding of the key issues that need to be addressed when considering presumptive joint custody reforms.

Legal vs. physical custody

Legislation establishing a presumptive right to joint custody should clearly state whether it applies to legal custody, physical custody, or both.

Definitions of joint legal custody and joint physical custody should be provided. The definitions should simply state, in broad terms, what the terms mean.  For example, “joint legal custody” could be defined to mean that responsibility for making major decisions concerning a child is shared by the parties; and “joint physical custody” could be defined to mean that physical custody, i.e., possession and responsibility for ordinary day-to-day decisions about care, is shared by the parties.

For example, “joint legal custody” could be defined to mean that responsibility for making major decisions concerning a child is shared by the parties; and “joint physical custody” could be defined to mean that physical custody, i.e., possession and responsibility for ordinary day-to-day decisions about care, is shared by the parties.

Reformers should avoid the temptation to try to make definitions do the work that is more appropriately done by a substantive enactment.

Defining joint physical custody to mean an equal division of time, for example, could have serious unintended consequences. It would force a court to issue a sole custody order even in situations where it might otherwise have been inclined to order joint custody. In the absence of such a limited definition, a court may be inclined to characterize an arrangement calling for a 50.1%/49.9% division of time as “joint physical custody.” If, however, the statutory definition of joint physical custody is amended to mean an equal amount of time, then the court would be required to classify the parent with 4,384 hours/year with the child as the child’s sole custodian, and the parent with 4,382 hours/year as the noncustodial “visitor.”

Moreover, if a couple undergoes a change of circumstance making an exactly equal division of time impracticable – such as an employer’s requirement that one of them relocate a considerable distance away – this, in itself, could then provide grounds for a motion to declare the resulting change in parenting time schedule has caused the order to become one for sole custody, even without any showing of grounds for modification.

The better approach would be to restrict definitions to their intended purpose, i.e., to define the meaning of terms. If you want to require courts to order a specified minimum amount of time for each parent in every case, then do that by enacting prescriptive legislation.

Parental rights

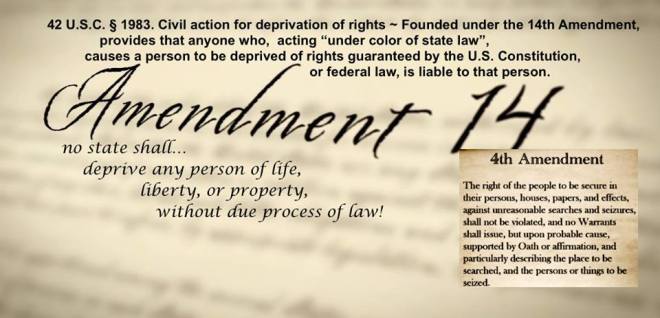

Based in part on a mistaken belief that parental rights are inconsistent with children’s rights, and in part on a movement toward greater legal recognition of non-traditional “de facto” families, the concept of parental rights has fallen into disfavor among a lot of policy-makers these days. Nevertheless, there is a long line of U.S. Supreme Court decisions recognizing that parents have a fundamental right to the custody of their children, and that states that deny parents this right violate the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Accordingly, presumptive joint custody legislation should be drafted in such a way as to be constitutionally compliant with the rights of parents to the custody of their children.

Unless the intention is for parents to be required to share custody with non-parents, a presumptive joint custody proposal should make it clear that it applies only in contests between parents.

Properly conceived, the purpose of presumptive joint custody legislation is to preserve the existing rights of both parents to the custody of their children unless good reason for terminating the custody rights of one of them is established. Historically, judges simply assumed that the divorce itself was good reason. That assumption, however, was based on a conception of children as items of property. Courts felt a need to allocate each item of property to one or the other parent, primarily for the purpose of clearing title to the property so that the validity of future transfers of title to others would be more certain. To the extent our civilization has progressed to the point that children are no longer viewed as items of property, a divorce should no longer constitute good reason for either extinguishing or restricting parental rights.

The opinions of child development and psychology experts about the relative benefits of sole and joint custody for children could be relevant and useful to the question whether presumptive joint custody should apply in custody contests between third parties. In these kinds of cases, neither party has a natural right to custody because neither party is a parent. Third-party rights to custody of children exist if and only if a court grants them. Since neither party in a third-party custody dispute has an existing right to custody, the court must decide the case entirely on the basis of a de novo evaluation of what is most beneficial for the child.  A list of “best interest” factors may be useful in these situations, as might a presumption favoring either sole or joint custody that is enacted on the basis of a consideration of the opinions of child development experts.

A list of “best interest” factors may be useful in these situations, as might a presumption favoring either sole or joint custody that is enacted on the basis of a consideration of the opinions of child development experts.

In disputes between parents, though, the impetus for presumptive joint custody legislation is not that a consensus has developed among experts that a greater quantity of contact with both parents is usually better for children’s development. That may well be true. But even if it could not be established that equal amounts of contact is either better or worse for children than sole custody is, the truths would remain that parents have a constitutionally protected right to custody of their children; that children are not property; and that they should not be divided like property in a divorce unless some constitutionally valid reason for terminating or restricting parental rights is demonstrated.

Grounds for rebuttal

Any enactment of a presumption must address the grounds that may be used to rebut it. In thinking about this, it is important to understand that facts that are relevant to joint legal custody are not necessarily relevant to joint physical custody, and vice versa. It is important, therefore, to address the grounds for rebuttal of each of these kinds of presumptions separately.

Legal custody

The grounds for rebuttal of joint legal custody should relate to decision-making.

It is not constitutionally permissible for a judge to substitute her own opinions about a child’s religious and educational upbringing for a parent’s. Instead, courts are constitutionally required to presume that parents act in their children’s best interests. Accordingly, a presumptive joint legal custody statute may authorize judges to find a presumption in favor of joint legal custody to be rebutted if there is evidence that a parent’s decisions about a child’s upbringing are harmful to the child, or that there is a risk that they will be.

Surprisingly few states have made this the basis for rebutting a presumption of joint legal custody. Instead, the most frequently listed basis for rebutting joint legal custody is “inability to cooperate.” Some even go so far as to shift the burden of proof to parents seeking joint legal custody to convince the court that they have this ability.

An inability to cooperate does appear to be relevant to joint legal custody, or at least more relevant to joint legal custody than to joint physical custody. If the parties are completely unable to cooperate, then they are not going to be able to make joint decisions concerning their children.

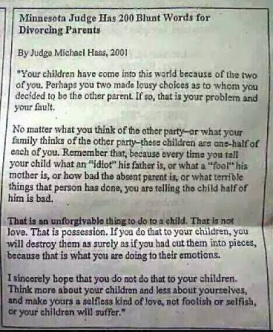

Care should be taken, however, to prevent over-application of the “inability to cooperate” grounds for rebuttal. Willingness to cooperate is completely within each party’s control. Because of this, it is very easily manipulated. A party seeking sole instead of joint legal custody may circumvent the presumption simply by refusing to cooperate with the other party. Therefore, it may be desirable to neutralize the benefit of an unreasonable refusal to communicate or cooperate. For example, the legislation could provide that a court may not make a finding of inability to cooperate or communicate on the basis of a party’s unreasonable refusal to communicate or cooperate.  A more aggressive approach to encouraging greater cooperation and communication would be to specify that a party’s unreasonable refusal to communicate or cooperate with respect to a major issue concerning the child shall be admissible as evidence of a need to assign sole decision-making authority with respect to that issue to the other party.

A more aggressive approach to encouraging greater cooperation and communication would be to specify that a party’s unreasonable refusal to communicate or cooperate with respect to a major issue concerning the child shall be admissible as evidence of a need to assign sole decision-making authority with respect to that issue to the other party.

Also, legislation should recognize that a present ability to communicate and cooperate may not always be necessary in order to reach decisions on issues going forward. A judge may include in the order a specified means by which a matter is to be decided in the event of impasse. In lieu of terminating one parent’s right to legal custody in the event of impasse, legislation might require the parties to attempt to resolve their disputes through mediation, or to submit their dispute to a parenting consultant who will make the decision for them on the basis of an independent evaluation of the child’s best interests. Yet another approach might be to allocate to each parent separate decision-making responsibility for specific kinds of decisions.

Physical custody

States that have enacted presumptive joint custody have made it rebuttable by showing that the parties are not cooperative. While it is clear that cooperativeness is relevant to joint legal custody, it is not clear why it is relevant to joint physical custody. Unlike major decisions affecting religion and education, a court may specify a parenting time schedule for the parties if they are unable to agree. Accordingly, there does not appear to be any rational basis for making a parent’s right to physical custody conditional upon a demonstrated willingness or ability to cooperate with the other parent.

Many proposals for presumptive joint custody also link it to the “best interest of the child” factors. By framing the presumption as an inference that joint physical custody is in the best interest of the child, they link rebuttal of the presumption to the factors set out in a state’s “best interest factors” statute.

One problem with this approach is that it will not really change anything. If joint custody is rebuttable by citing any of the factors set out in a “best interest” statute, then custody cases will continue to be about who scores highest on the statutory “best interest” factor(s) that a particular judge decides to hone in on in a particular case. The same problem of unreviewable exercises of judicial discretion to circumvent parental rights will continue to exist.

According to the United States Supreme Court, courts must presume that parents act in their children’s best interests, and judges must be careful not to substitute their own views about which lifestyle choices and care-giving styles and patterns are best for a child, in place of a parent’s. Yet “best interest” statutes invite, or even require, judges to do just that.

Remember, too, that the formulation of most of these factors occurred during a time when courts assumed that children, like all other marital property, needed to be distributed to one or the other parent upon divorce. The reason for setting these factors out in statutory form was to require courts to cite some basis other than sex for declaring one, and only one, parent the winner of an “award” of the category of marital property consisting of children. They were not designed to address the question whether sole or joint custody is in a child’s best interest.

Rather than tying rebuttal to the statutory “best interest factors” list, then, some thought should be given to the kinds of facts that should need to be proven in order to justify a refusal to preserve a particular parent’s natural right to custody of her child, keeping in mind that whatever reasons are ultimately selected should not be such as would involve a judge in substituting his or her own opinions about what is in a child’s best interests in place of those of a parent.

Guidance in this respect might be found in a state’s statutes pertaining to the circumstances in which a court may restrict a parent’s access to her children, or order supervision of a parent’s time spent with a child. Grounds vary from state to state, but may include such things as abandonment; inadequate supervision; incarceration; physical or sexual child abuse; causing or permitting mental injury to a child; physical, educational or emotional neglect; medical neglect; inadequate control over a child (habitual runaway, e.g.); mental or emotional abuse; exposure to domestic violence; habitual drug or alcohol use impairing parenting ability; mental illness, mental deficiency or emotional disturbance that places a child at risk of physical or mental injury; endangerment; encouragement or approval of a child’s criminal act; a lengthy out-of-home placement; chronic and unreasonable interference with a parent’s custody or visitation rights; disparagement of the other parent; or risk of child abduction.1

Of course, the parties’ agreement to a sole custody arrangement should also be deemed a sufficient basis for rebutting the presumption.

Standard of proof

Presumptive joint custody legislation should also address the standard of proof that is required in connection with rebutting the presumption.

The three basic standards of proof, in order from the easiest to the most difficult to satisfy, are: preponderance of the evidence; clear and convincing evidence; and proof beyond a reasonable doubt. “Reasonable doubt” is applied in criminal cases. The other two generally are applied in civil cases.

The “clear and convincing evidence” standard is normally required in cases where an equitable remedy is sought, or where a constitutionally protected fundamental right is implicated.

Structuring time when joint physical custody is ordered

Legislation establishing a presumption in favor of joint physical custody does not need to address how time with the children will be structured between the parties. It may simply state the existence of a presumption and then leave it to the parties to decide upon a physical placement schedule.

In the interest of reducing litigation, however, a state enacting presumptive joint physical custody may want to consider establishing, in addition, some method or guideline for allocating time between the parties.

One approach would be to require the order to either establish a schedule or specify the means by which the parties will develop their own (e.g., mediation, parenting consultant, etc.)

Another approach would be to require the parties to submit a parenting plan to the court with specific provisions relating to the allocation of parenting time and decision-making responsibility to each party. Each party could be required to submit a plan separately if they are unable to agree on one, leaving it to the judge to decide between them or to impose one of his own making.

Because there will always be cases in which the parties are unable to agree, there will always be a need for a standard by which a judge is to make these kinds of decisions when called upon to do so.

A preference for an equal or substantially equal division of time is one idea for a standard. On the other hand, some believe that a goal of joint custody should be to make a child’s postdivorce life as similar as possible to his pre divorce life.2 For those who adhere to this view, the ALI’s approximation rule would be the appropriate standard. As an alternative to either approach, a legislature could develop a list of factors relevant to the allocation of physical time between two parties, such as geographic proximity; the parents’ work schedules; the children’s school schedules; the wishes of the parents and the children; transportation needs and capacities; impact of a proposed schedule on a child’s physical or emotional health, well-being and development; or possibly other factors.

In addition to, or instead of, any of the above, legislation might specify a minimum amount of time to which a joint physical custodian shall be entitled. For example, legislation might provide that unless they agree otherwise, each joint physical custodian is presumptively entitled to at least X percent of the parenting time (where “X” represents the desired minimum.)

Care should be taken to ensure that standards affecting the allocation of time between joint physical custodians are not conflated with standards relating to the right to physical custody. For example, the fact that a parent lives a great distance away from the other parent could be an important consideration when developing a schedule of alternating periods of physical placement between joint custodians, but it does not logically follow that it is also a reason for denying a parent joint custody of her children.

Agreements

Substantive due process mandates a presumption that parents act in their children’s best interests. Legislation, therefore, should make it clear that courts normally must approve parental custody and parenting time agreements unless they are found to be harmful to the children. The legislation should also be clear about the circumstances under which a court may reject the parents’ agreement. Those circumstances should include not only a finding of harm, but also ordinary contract defenses like fraud, mistake and duress.

Existing custody statutes typically permit a court to adopt the parents’ agreement “if the court determines it is in the best interests of the child.” In so providing, they essentially mandate courts to substitute their own judgments about what is best for children for those of the children’s parents. This nullifies the constitutionally mandated principle that parents must be presumed to act in their children’s best interests. Therefore, a legislature that is concerned about the constitutionality of the laws it enacts may wish to consider the propriety of statutory language giving courts broad powers to substitute their own opinions in place of the parents’ determination of what is in their children’s best interests.

Example. State A has enacted a “best interests” statute that lists, as factors court must consider when deciding custody, “which party has been the child’s primary caretaker.” The statute further provides that a court must approve the parents’ agreement as to custody unless it is not in the child’s best interests.

Now State A enacts a presumption in favor of parental joint legal and physical custody, rebuttable by evidence that it is not in a child’s best interests. Tom and Katie submit their joint custody agreement to a judge in State A. The agreement acknowledges that Katie has been the primary caretaker, but states that they plan to share responsibilities almost equally now. Both parents are equally fit, and neither has harmed or is a danger to their child. They await the judge’s decision.

Reviewing the agreement, the judge believes it would be harmful for the child to be “shuttled back and forth” between homes. He has no evidentiary basis for this belief; it’s just something he once read in a bar association article that was penned by a sole-custody advocate. If the presumption has been framed solely in terms of the “best interest” standard, the judge may actually cite the agreement as a basis for an award of sole custody to Katie if the state’s “best interest” statutes lists “which parent has been the primary caretaker” as one of the factors. Many do.

In short, presumptive joint custody legislation should take care to ensure that statutory provisions relating to agreements to share joint custody are subject to judicial nullification only on the basis of the kind of finding that would suffice to rebut the presumption in favor of joint custody.

One more thing to consider about agreements: If a particular kind of division of time (e.g., an equal time requirement, the approximation rule, or a presumptive minimum) is specified in a presumptive joint custody proposal, then the proposed legislation should address whether the presumption will continue to apply in the event the parents agree to a different allocation of time.

Dispute resolution

Mediation or some other means of resolving disputes about major decisions affecting the child is critical to the viability of joint legal custody.

It also may be useful for resolving disputes about joint physical custody schedules.

Unlike physical custody or visitation, where parties may have recourse to the courts to resolve a dispute for them if they are unable to agree, a court is not well equipped to make major decisions about children’s education, health care and religious upbringing in the event the parents are unable to agree. Indeed, courts are constitutionally prohibited from making certain kinds of decisions for parents. For example, the First Amendment prohibits courts from choosing a church or a particular religion for a child. Accordingly, any legislative enactment establishing a rebuttable presumption of joint legal custody ideally should address how a decision is to be made in the event the parties cannot reach agreement on a major decision affecting the child.

One approach would be to require a court to assign final decision-making power to one of the parties in the event they are unable to reach an agreement on a particular major educational, religious or health-care decision affecting the child.

The drawback to giving one party “the final say” over all decisions is that it is effectively the same thing as granting that party sole legal custody.

The drawback to giving one party “the final say” over all decisions is that it is effectively the same thing as granting that party sole legal custody.

An alternative would be to require a court to allocate final decision-making power over different kinds of decisions between the parties (e.g., assigning one party the final say in health-care decisions, while the other party has the final say in matters of education and religion.)

Yet another approach would be to require the parties to attempt mediation. If mediation is unsuccessful, or if the parties agree to forego it, a court might appoint a parenting consultant with the power to make binding decisions for the parties.

To encourage cooperation and reasonableness during dispute resolution processes, legislation might provide that an unreasonable refusal to cooperate in joint decision-making may be grounds for an award of sole legal custody to the other party.

Move-aways

Many states, although not prohibiting interstate moves by parents, require a custodial parent to obtain either the other parent’s permission or a court order determining that the move is in the child’s best interests. The language in a particular state’s move-away statute may need to be revised if rights and obligations are couched in terms of “the custodial parent” and “the noncustodial parent,” but is silent about joint custodians. A joint physical custodian should not possess any greater privilege to move out of state without the other parent’s permission than a sole custodian enjoys. By the same token, joint physical custodians should have at least as much power to grant or withhold permission for the other parent’s move as a noncustodial parent enjoys.

The standard that courts apply to determine whether a move to a different state or foreign country is in a child’s best interests may also need to be revised. The courts of some states presume that a custodial parent’s move is in a child’s best interests if it is beneficial to the custodial parent. The legislature in a state in which courts have adopted this rule may need to assess whether the rule needs to be altered to take account of the possibility of joint physical custodians. When there are joint custodians, which custodial parent’s interests is a court to consider – the one who is moving, or the one who remains? It would not seem to be possible to decide the issue on the basis of the best interests of both parents, since their interests in this situation conflict.

Rethinking the underlying idea of equating a child’s best interest with what is in the custodial parent’s best interest also might not be a bad idea.

Modification

A legislature adopting a joint custody presumption should consider its impact on the standard for modification of custody. Most states draw a sharp distinction between the standards applicable to modification of custody and those applicable to modification of a parenting time schedule. Legislatures typically have set the bar very high for modifications of custody. In many states, merely showing that a change to the custody order is in a child’s best interests will not be enough. Unless the parties agree to the change, it will be necessary to establish, in addition to the fact that the change is in the child’s best interests, proof of endangerment or impairment of the child’s health or safety. By contrast, modifications of parenting time rights or a parenting time schedule may be made at any time, requiring only a showing that a requested modification is in the child’s best interests.

The issue of the allocation of physical placement time between joint physical custodians is really not different, in substance, from the issue of how physical placement time between a custodian and a person with visitation rights is to be allocated. There would be no logical reason, therefore, for applying one standard to a requested alteration of the parenting time schedule in one situation, and an altogether different standard in the other.

Example 1. Under their custody order, Grace has sole physical custody and Will has visitation rights. The order provides that Will is to have the children on weekends and Grace is to have them during the week. Will’s employer changes his work schedule to require him to work weekends. Will therefore brings a motion asking the court to substitute some other days in place of his weekends with the children.

Example 2. Same as Example 1, except that Will and Grace are joint physical custodians.

Under the facts in Example 1, Will should be allowed to proceed with his motion to modify the schedule. Visitation time is presumed to be in children’s best interests; the change in work schedules prevents it; so the only logical thing to do is change the visitation schedule to non-weekend days.

Under the facts in Example 2, though, a court might be required to dismiss the same motion if the state has a statute prohibiting custody orders from being modified in the absence of a showing of something extreme like endangerment.

Legislation could prevent this anomaly by making the parenting time schedule provisions of a joint custody order modifiable upon a “best interest” showing rather than the more onerous “endangerment” standard.

If this approach is taken, then some thought should be given to whether this will give courts the power to reduce a joint physical custody arrangement to one that is little different from a sole physical custody order, in terms of the amount of time each parent receives. Should a joint custodian be permitted to reduce the other joint custodian’s time from 50% to 14% merely on the basis of an argument that doing so would be in the child’s best interest? If so, then it would be possible for one parent to effectively reduce the other parent to the traditional “visitor” status (14-percenter) without having to meet either the appropriate standard for rebutting the presumption of joint physical custody or the standard for modification of custody.

One way to resolve this dilemma would be to require the application of the more onerous standard for modification of custody in those cases where a parent seeks either the elimination or a substantial reduction of the other parent’s time. The lower-threshold “best interest” standard could be reserved for cases in which only minor changes to the schedule are sought.

If this approach is taken, then to avoid uncertainty it might be a good idea to specify some objective measure for determining when a change is substantial enough to require application of the custody modification standard. One way to do this might be to specify a maximum percentage of change in parenting time that may be sought before the custody modification standard kicks in.

Another change to modification statutes that should be considered if presumptive joint custody is enacted has to do with the grounds for modification. Specifically, it might be desirable to add to the list of grounds for modification of custody the fact that something which previously militated against an award of joint custody no longer stands in the way of an award of joint custody. Under many existing statutes, a showing of endangerment or impairment of a child’s physical or emotional health has to be made in order to get a change of custody. A showing that a party is no longer a danger to a child would not be a sufficient basis for a modification of a custody order under a statute worded in this way. For example, if a mother can show that she has successfully rehabilitated herself from an addiction to Vicodin, then it should be possible for her to ask the court to modify a previous order that granted sole custody to the father on that basis so that it restores both parents to the status of joint custodians.

In short, the modification statute should specify a standard for modifications from sole to joint custody, not merely for modifications from one sole custodian to a different sole custodian.

Coordination with other laws

A state legislature considering a joint custody presumption should review the wording of its child support and public assistance statutes to ensure there are no unintended consequences. For example, in many states, statutes relating to child support enforcement speak in terms of enforcement on behalf of “custodial” parents, or the obligations of “noncustodial” parents. This could have unintended consequences not only in terms of the ability of a joint custodian to enforce child support rights, but also in terms of the ability of a joint custodian to avail himself of certain programs and defenses that a statute only makes available to a “noncustodial” parent.

Some public assistance programs limit eligibility to persons with whom the child primarily resides. Determining primary residence may be difficult if both parents are awarded physical custody. To ensure that joint custodians are not denied public assistance benefits for which sole custodians are eligible, it may be desirable to require joint custody orders to designate one or both of the parties’ homes as the child’s primary residence. Alternatively, a legislature may wish to review the wording of its public assistance eligibility statutes.

Applicability to existing orders

If legislation establishing presumptive joint custody is enacted, a question naturally arises about the effect it will have on existing orders that were issued without the benefit of the presumption. Accordingly, a legislature will want to consider whether, and under what circumstances, the change in the law should be treated as grounds for modification of an existing custody order.

- See, e.g., MINN. STAT. §§ 518.175, 518.176 (2012); Abu-Dalbouh v. Abu-Dalbouh, 547 N.W.2d 700 (Minn. Ct. App. 1996) (imposing restrictions on visitation based on risk of abduction); cf. Al-Zouhayli v. Al-Zouhayli, 486 N.W.2d 10 (Minn. Ct. App. 1992) (requiring proof of strong probability of abduction if the risk of abduction is the basis for a restriction on visitation.)

- See J.S. Wallerstein & S. Blakeslee, SECOND CHANCES: MEN, WOMEN, AND CHILDREN A DECADE AFTER DIVORCE (1989); R.D. Felner & L. Terre, Child custody dispositions and children’s adaptation following divorce, in PSYCHOLOGY AND CHILD CUSTODY DETERMINATIONS 106-53 (L. A. Weithorn ed., 1987)

Source: The Future of Custody Law Reform | Law Blogs

——————————————

My book, The History of Custody Law, is available in paperback and Kindle e-book formats at Amazon.com: Purchase The History of Custody Law

Definitions

Definitions

LEARN FROM THE WORST ALIMONY LAWS IN THE UNITED STATES

LEARN FROM THE WORST ALIMONY LAWS IN THE UNITED STATES

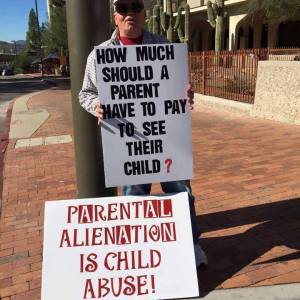

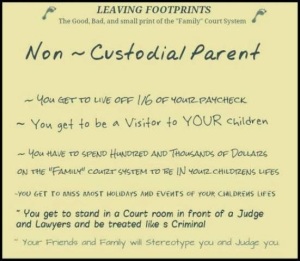

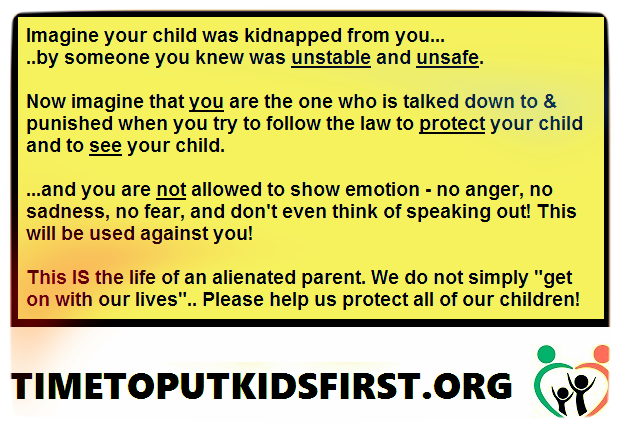

Our Constitutional right to bear arms is front and center in state and federal legislatures. But where is the debate on protecting our basic human rights to parent our children? (also constitutionally protected by the 14th amendment) Every day in every state, mothers and fathers lose their basic human right to parent their children.

Why? Because the divorce industry wants your family’s money! Estimated at $170 Billion annually! How? We all have a family member, friend or neighbor who has been through a nasty divorce. Most of us believe children need both parents equally and that there exist a standard of 50/50 custody that the courts start from.

NOT TRUE!!!! THERE IS NO PARENTING TIME STANDARD!!! THIS LACK OF STANDARD CREATES 90% OF ALL DIVORCE CONFLICT AND DIVORCE LITIGATION!!! IT DESTROYS FAMILIES AND LIVES!!! STOP IT NOW!!!!!

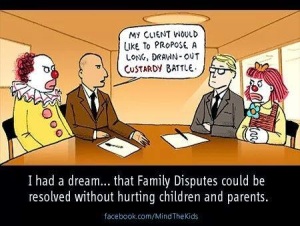

In litigated divorce, there is no standard as to how children should spend their time between parents. The lack of a parenting time standard causes our children to be viewed as a prize where unethical lawyers and custody evaluators use them as pawns between parents. If there were a parenting time standard, it would resolve over half of divorce litigation taking place right now.

MAKE PRESUMPTIVE 50/50 THE REBUTTABLE STANDARD AND ELIMINATE CUSTODY EVALUATIONS

Start with the presumption that both parents are fit and entitled to an equal role in their children’s lives. This presumption is rebuttable only by findings of fact based upon a preponderance of evidence in abuse, neglect or addiction. Everything else unconstitutionally denies parents their rights to parent children.

ONLY OUR LEGISLATORS CAN PROTECT US FROM THE DESTRUCTION OF DIVORCE WITHOUT OBJECTIVE AND EQUAL STANDARDS

The divorce industry is $170B annually and motivated to oppose standards so they can create, promote and perpetuate conflict to increase billing hours exponentially. Have you ever heard “It’s only the lawyers who win in divorce”?

Add to lawyers: custody evaluators (duplicate roles in some states), criminal lawyers, courts, psychologists, therapists, investigators, GALs, an entire cottage industry of brokers! With overdue and demanded, simple and just changes to state statues, families and children can be forever protected from the ravages of the divorce industry by a simple and equal standard. The lack of a presumptive 50/50 rebuttable standard destroys lives and families, often forever. Children as pawns can be scared for life, arbitrarily lose a parent, or two, for life and are in much greater peril in life. Mothers and fathers lose their children and react badly. Suicide and homicide is not uncommon. Mothers and fathers can be jailed for protecting their children or going bankrupt. http://www.causes.com/campaigns/44294-enact-uniform-parenting-time-guidelines-separated-parents

LikeLiked by 5 people

LikeLiked by 4 people

LikeLiked by 4 people

LikeLiked by 3 people

LikeLiked by 3 people

LikeLiked by 2 people